The choir of the First Baptist Church in 1918 stand with Reverend B. F. Parks on the porch of the church. Texas State University English Professor and President of the Calaboose African American Museum Dr. Elvin Holt will give a presentation about the African-American men and women that contributed to the musical legacy of the Dunbar neighborhood at “Making a Joyful Noise in the Dunbar Neighborhood: 1918-2018” on Thursday, Nov. 1 from 7 to 8 p.m. at the San Marcos Public Library. Photos courtesy of Dr. Elvin Holt

'Making A Joyful Noise'

For more than 100 years, African Americans in the Dunbar neighborhood have nurtured a remarkable legacy of both sacred and secular music. The roots of this rich musical tradition can be traced back to the first enslaved men and women who brought with them the inspiration for work songs, spirituals, ring shouts and field hollers, precursors of musical genres such as ragtime, blues, gospel and jazz.

Dr. Elvin Holt, Texas State University English professor and president of the Calaboose African-American Museum, will discuss the contributions that local African-American men and women made to that musical legacy at “Making a Joyful Noise in the Dunbar Neighborhood: 1918-2018” on Thursday, Nov. 1 from 7 to 8 p.m. at the San Marcos Public Library.

“When the slaves were brought to America from Africa, they brought with them a very strong impulse to make music; that wasn’t new to them,” Holt said, “that was one of the things that their captors and masters could not take from them – it was in their head. They couldn’t rob them of their desire to make music and I think the entire African-American tradition has its roots in the African music that was shared on the plantations. They later became blues and jazz and gospel and just influenced a number of musical styles.”

According to Holt, America has long overlooked the musical contributions that African culture made. Even the quintessential American instrument, the banjo, came to America with the slaves and musicologists have long looked in West Africa for its predecessors. But the more overlooked part of African-American musical history, according to Holt, is of the local sort. The music that came from historically Black neighborhoods, like the Dunbar neighborhood, that united and built community and created leaders.

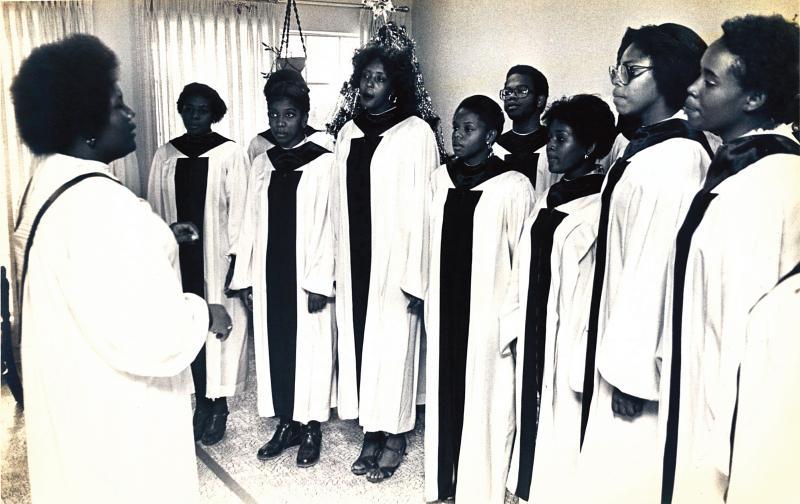

Pat Moore (far left) was the director of a mass community choir in the Dunbar neighborhood in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Holt will talk about those men and women in Dunbar, that played and created and performed music through years of segregation and discrimination.

Holt said one of the first major contributors to the Dunbar neighborhood’s musical lineage was the Cephas family, of the historic Cephas House on MLK Drive. The Cephas family was a family with music in their blood; the first string tying them to the history of Dunbar is a photograph of the First Baptist Church choir in 1918 that has both Ulysess Cephas and his wife Cora Willie pictured.

Later in the 1930s, Cephas, a coronet player, taught other men in the Dunbar neighborhood how to play band instruments, eventually assembling a full marching band – the San Marcos Independent Band – that played Juneteenth celebrations and marched with local masonic groups and churches. The San Marcos Independent Band played until 1952, when Cephas passed away. Their son Willie Cephas went on to play in the San Marcos Independent Band as well.

The Cephas’ daughter Johnnie Cephas Rutledge also had a penchant for music and wanted to learn to play piano – something that wasn’t easily accessible to a young African-American girl in the 1920s.

“When she wanted to learn to play piano in the 1920s there was no one to teach her except someone at Southwest Texas (now Texas State University),” Holt said. “In the 20s of course, they were segregated. Mr. Cephas asked one of the members of the music department if she would teach his daughter to play piano and the lady said that she would, but when the music department chair found out about the lessons, he told her she couldn’t do that. If she taught this Black girl how to play, she would be fired.

“The professor then told Johnnie to come to her house in the evening and she would teach her at home, but she would have to come through the back door. Mr. Cephas and Cora encouraged Johnnie to study with her, even though she had to go through something that was very demeaning. That’s what she had to do to get the lessons.”

Rutledge went on to be a music teacher, eventually moving to Palestine, and was alive to see her home designated as a historic landmark in the Dunbar neighborhood.

“She came up against discrimination and racism in a very real way,” Holt said.

Citywide choirs, community choirs or mass choirs were also a tradition among African-American communities during the early to mid 20th Century, according to Holt. Citywide choirs were an assembly of multiple churches’ and organizations’ choirs that performed.

One of the first citywide choirs in the Dunbar neighborhood was directed by Grace Sanders; she directed mass choirs in the Dunbar community for 60 years.

“She’s one of the ladies with the longest service in music in the Dunbar community and she was a mentor for many of the younger musicians that came up after her,” Holt said.

A community choir sings at the Greater Bethel Baptist Church on Centre Street in the 1970s.

Sanders was also the music minister at Greater Bethel Baptist Church. Pat Moore also directed Community Choirs in the Dunbar neighborhood in the late 70s and 80s. Citywide choirs flourished in the Dunbar neighborhood into the 80s.

Holt will also touch on singing groups like the The Imperial Harmonizers, a quartet made up of James E. Smith, George E. Smith, Alonzo Hardge and Willis Callihan that started in the 1940s and performed throughout the area into the 1980s.

Holt said groups like the Imperial Harmonizers were not uncommon amongst African-American communities in the early to mid 20th century.

“These were always Black men who had no formal musical training, that would get together and based on what they heard on the radio or recordings, they would develop their own style and go out and perform in Black communities, mostly in churches,” Holt said.

The "Imperial Harmonizers" was a quartet made up of James E. Smith, George E. Smith, Alonzo Hardge and Willis Callihan. They performed from the 1940s into the 1980s.

Holt will also cover current music in the Dunbar neighborhood, including current Pentecostal Temple Church-God Minister of Music Wayne Thompson and other leaders in the African American community that are still playing, singing and performing.

“The thing to me is this is all gone; there is no community choir anymore in San Marcos; there’s no marching band anymore, there’s no Imperial Harmonizers anymore, so the younger people have no idea that this ever existed,” Holt said, “and I think it is so important that we document their service to the community, otherwise they will be forgotten.

“My main purpose is to open up to people an aspect of African- American history in this local community that would otherwise be ignored or totally unknown.”