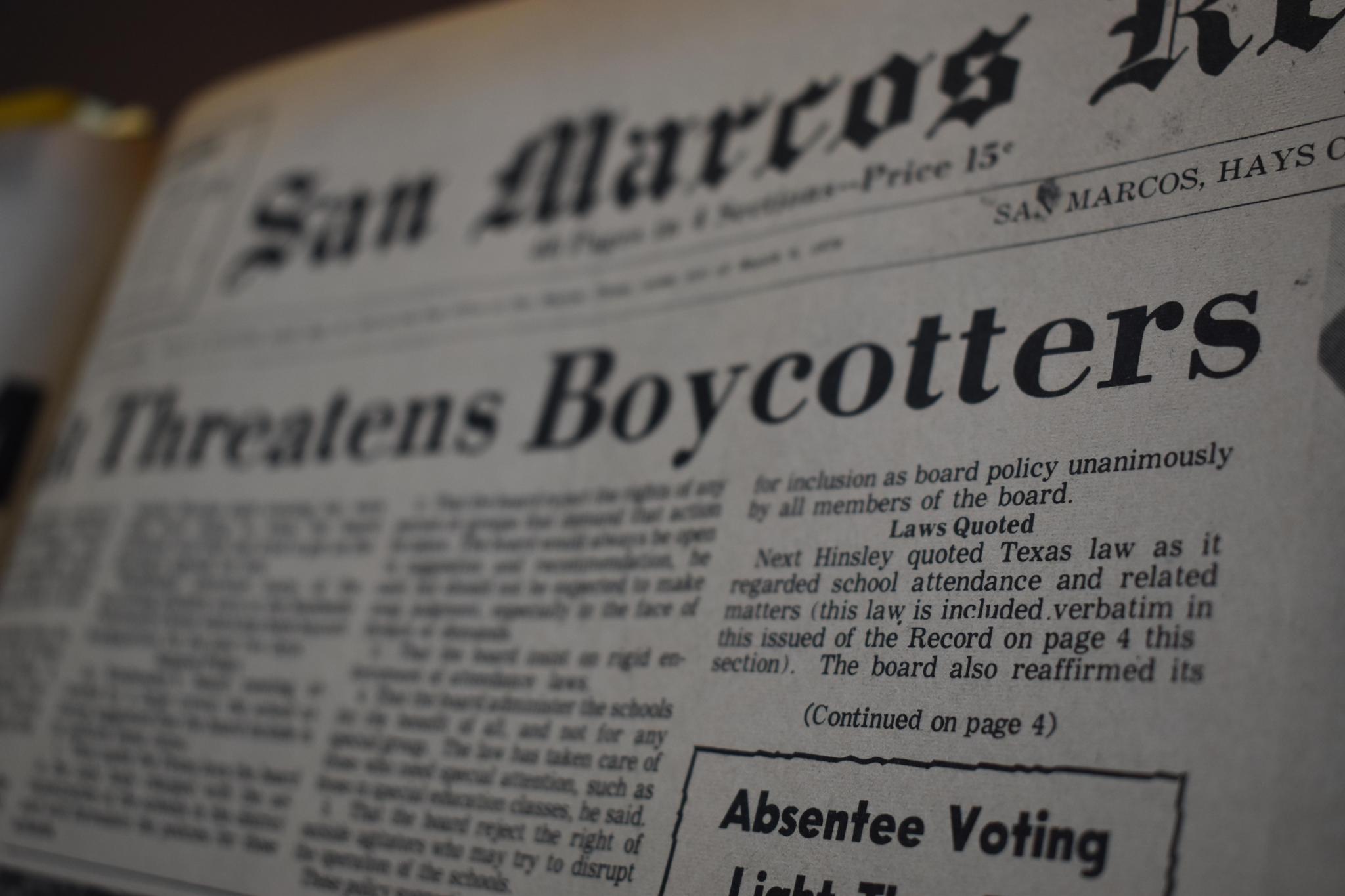

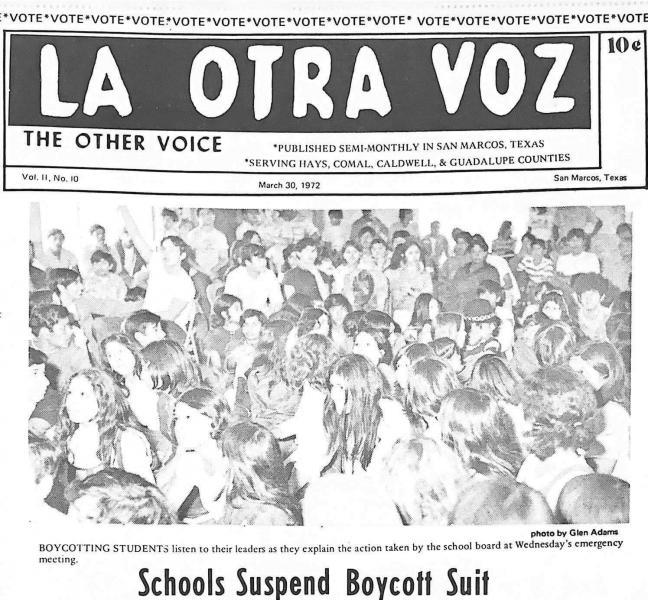

Fifty years ago this month, students from the San Marcos High School and Goodnight Jr. High School walked out of their classes as part of a boycott against the schools for not cooperating with the students’ list of grievances. Above, a headline from the San Marcos Daily Record covering the walkout. Daily Record photo by Alyssa Gonzales. Below, La Otra Voz — a semi-monthly newspaper publication that highlighted and informed the Mexican American communities of the Hays, Comal, Caldwell and Guadalupe counties — cover the boycott. Scanned copy from the San Marcos Public Library archives

50 YEARS LATER: A look back at San Marcos’ school walkout

Fifty years ago this month, students from San Marcos High School and Goodnight Junior High School walked out of their classes as part of a boycott against the schools for not cooperating with the students’ list of grievances.

Inadequate special education classes, lack of Chicano and African American books in libraries, lack of Mexican American and African American staff, dress codes and lack of counseling for minority students were among students’ grievances.

In March 1972, San Marcos students boycotted for nearly a week to protest the unequal treatment and education opportunities they were facing.

“I went to a counselor for help on how to apply to go to college and she basically told me that I was not college material and that I should consider becoming a secretary,” said Bobbie Garza-Hernandez, former SMHS student and owner of Pink Consulting.

Garza-Hernandez went on to add that many other minority students faced this problem and were encouraged to work trade jobs rather than obtain higher education.

School walkouts in South Texas began in the late 1960s, with one of the first being the Edcouch-Elsa High School walkout in 1968, led by student Héctor Ramíerez to protest against poor treatment and unequal opportunities that Mexican American students faced.

According to ‘The Impact of Brown on the Brown of South Texas: A Micropolitical Perspective on the Education of Mexican Americans in a South Texas Community’ by Miguel A. Guajardo of Texas State University and Francisco J. Guajardo of the University of Texas-Pan American, Ramíerez took inspiration from organized labor unions and how they addressed poor working conditions while working in Detroit over the summer. Once Ramíerez returned to school in the fall, he led over 150 students in protest to further challenge the authorities of the education system.

That event, along with the Chicano Movement of the 1960s that saw protests and school boycotts to combat the unfair treatment and inequality of Mexican American students around the country, managed to trickle its way down to the South Texas area.

San Marcos’ boycott saw support from parents, white and African-American students, Southwest Texas State University students and local organizations such as the local Mexican-American Youth Organization (MAYO) chapter.

“I think there was a feeling that Latinos were targeted more. But, it was part of the whole thing with just general dissatisfaction with the school administration, that it did not listen to minorities,” said Juan R. Palomo, former art teacher at SMHS and former co-editor of La Otra Voz newspaper.

During a school board meeting, an ultimatum was given to students by school attorney J.C. Hinsley, that if students didn’t return to school on Thursday, March 23, 1972, legal action would be taken by the district, which called for a temporary injunction and restraining order against the boycotters and their supporters.

“They accused me of encouraging people to skip school that day, which I didn't,” Palomo said. “I was obviously in favor of what they were doing but I knew that it would have been ridiculous to actively, you know, encourage people not to go to school.”The majority of the school board voted in favor of this with the exception of board member Ofelia Vazquez-Philo.

She reflected on these events in 2016 prior to her passing in an oral history interview with The Portal to Texas History, a digital repository hosted by the University of North Texas Libraries and made available through the TCU Mary Couts Burnett Library.

“[The boycotters] asked if I was in favor and of course I was, yes. ‘Would you be in favor of this?’ Yes, of course, of course I was in favor, we needed to do something to wake them up, wake the opposition up, you know, those who wanted to keep us down,” Vasquez-Philo said.

A March 30, 1972 edition of La Otra Voz — a semi-monthly newspaper publication that highlighted and informed the Mexican American communities of the Hays, Comal, Caldwell and Guadalupe counties — reported the students ignored the ultimatum. During the boycott, students attended classes at the Southside Community Center taught by college students and members of MAYO. Meals provided by “merchants and Southside sympathizers.”

While the district did file a complaint against the boycotters and their supporters, including Palomo, the legal action was ultimately suspended and negotiations were agreed to be set regarding the grievances that the students initially requested.

An agreement was also reached that students would return to classes the following Monday with no “punitive measures” taken against them. A grievance committee was also formed that consisted of students, supporters, school board members and others.

“I continue to be impressed by the leadership of the Mexican American community, the men and women that I continue to have a lot of respect for,” Palomo said. “They were wise, they were committed and they stood behind the students. Some of them had sensitive jobs that they risked losing, but they did what they felt they had to do.”

Reflecting upon today's events, Palomo sees the boycott as more relevant than ever.

“There are still students that are being discriminated against and I think students in particular need to know that there was a time when students like them, their age, their same economic situation, stood up and said, ‘No, we won't take it anymore,’ and that their parents supported them and there was change as a result of that,” Palomo said.