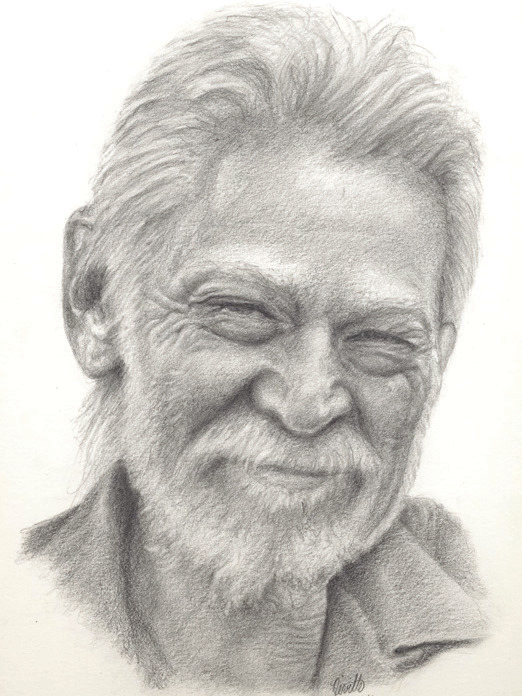

Dr. Grady Early, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, taught math and computer science at Texas State University for 29 years, serving briefly as interim chair of the newly-formed Computer Science department. After retirement, Early began researching his family history and gained some familiarity with various research tools: ancestry, familysearch, newspapers, San Marcos Record archives, findagrave and many more. This made it easy for him to segue into the histories of non-family members, which is how he began to write a story about Southwest Texas Normal in San Marcos, also known as San Marcos Normal, which is now Texas State University. This series will highlight the first staff at Southwest Texas Normal.

The 1907 Pedagogue described Thomas Green Harris in this way: “Harris (dear fossil) is a live spelling book. It is spoken in his action, and told in his look.”

Harris was born in 1854 on a farm in Monroe County, Tenn. His childhood education was gained in local Monroe County schools, followed by A.B. and A.M. degrees from what is now Carson- Newman University in Jefferson City, TN.

Harris’ first teaching job, probably one year, was in the public schools in Gilmer County, Georgia. In 1879, he was GTT — Gone to Texas — where, in 1880, he was a teacher in Weatherford. From there, his teaching career resembles a bus schedule:

• 1881-1883 Superintendent, Weatherford

• 1883-1887 Superintendent, Mansfield and Plano

• 1887-1891 Principal, Dallas High School

• 1891-1893 Superintendent, Dallas public schools

• 1893-1895 Principal, Houston High School

• 1895-1903 Superintendent, Austin public schools All of that public school service had made Harris keenly aware of the inevitability of a new normal school in San Marcos. Harris had seen the success of the first two Texas normals, at Huntsville and Denton, and he wanted to put his own stamp on Normal 3. It almost didn’t happen (according to San Marcos Record, Nov. 1, 2024, p. 5), but “almost” only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades. Gov. Joseph Draper Sayers had signed the enabling legislation for SWTN in 1899; although he left office on Jan. 20, 1903, he still had some political clout. He was unable to prevent a senate fight when Sen. Asbury Bascom Davidson, of DeWitt, attempted to prevent Harris’ selection as first Principal of SWTN, but he was able to limit the damage to a small monetary crisis when an “enrolling error” reduced SWTN’s budget from $18,000 to $1,800, a move that impacted almost everything including pay for the new faculty.

Harris was duly appointed and began, or continued, selecting faculty. After 16 years in various levels of public education, Harris had firm ideas about what was needed in a public school teacher. Naturally, they needed a firm command of their subject matter, but they needed to know HOW to teach. Harris proposed to do that with faculty who were themselves seasoned hands at the teaching game.

These were not folks with ink still wet on their diplomas. They all had teaching experience, many in positions of authority. Two had been superintendents, two had been president of Coronal Institute, one had been a department chair. Two were lawyers. One was Gov. Sayers’ half-sister. And Harris knew them all.

They were prepared to make SWTN a success, and they did. Despite various obstacles.

The chosen construction site for the main, and only, building turned out to be over one of San Marcos’ caverns. It absorbed a huge quantity of concrete, slowing the work and raising the cost. On May 15, 1902, the contractor reported that work was progressing very well, and he expected to finish on schedule. On July 9, 1902, completion had slipped to January of 1903, in time for a halfyear session of the Normal. On Jan. 3, 1903, Gov. Sayers delayed organization of the faculty because the building was not completed.

On May 26, 1903, Harris was optimistic that school would open in September. They had drilled a well, had lights in the building, retaining walls and walks were yet to come. It was not until 1908 that Main and Science got “water closets.” The path to the privy would be a thing of the past.

There was other work to be done. Three hundred and three students would show up, but there were no dormitories. Eager to reap the rewards of a new customer base, the citizens of San Marcos formed a committee to scour the area for those with an extra room or two and willing to rent them to students. Many students were from San Marcos, of course, and stayed at home. Others had come from some distance. After all, one of the rationales for SWTN was that the other two Normals were too far away from most citizens of Texas. Situated midway between Austin and San Antonio, there were a large number of students expected from those towns.

Harris and the other faculty defined the curriculum and printed the first Announcement, equivalent to today’s Catalog. There were 24 pages of vital information, including stern warnings: “Only those desiring to prepare for the great work of the teacher should come to the Normal;” and “If you ... , do not come to the Normal.” That elipses represents several types of students that Harris did ... not ... want.

The students that he did want kept coming in increasing numbers. Harris bore it all with equanimity. He was jovial, fair, firm and absolutely pig-headed about alcohol; he was a Southern Baptist, after all, and conducted daily chapel classes.

Then, the 1910 gubernatorial election reared its ugly head. Or, rather, the Democratic primary; Texas was solidly Democratic: win the primary and the governor’s race is over.

In 1910, there were five Democratic candidates for governor. Oscar Branch Colquitt was, by far, the leading candidate, and he was not a prohibitionist. It’s hard to collect taxes on liquor if liquor has been outlawed.

As one paper put it, “Democrats who support [Colquitt] have temporarily exalted the liquor interest above democracy.”

Nevertheless, in the Democratic primary, Colquitt got a nice plurality, 41%, with the rest split among four other candidates.

Colquitt’s opponents in the general election were even less fearsome. J.O. Terrell was a Republican; little chance. Reddin Andrews was a Socialist; less chance. Colquitt got 79.8% of the vote.

Harris had not supported Colquitt; it is said that he supported Colquitt’s opponent, which one is not known. More likely, it was Harris’ firm and, some say, insulting Open Letters to Colquitt that appeared in many newspapers statewide, that raised Colquitt’s hackles. In the event, Colquitt won and promptly asked for Harris’ resignation.

Colquitt took office in January of 1911; Harris resigned in May of 1911. Or, at least, announced his resignation. His successor Cecil Evans took office on Sept. 1, 1911.

Harris walked across the street to the San Marcos Baptist Academy, on what is now West Campus, and became its second president, serving until 1916. When he retired. Briefly.

In 1918, with Colquitt safely out of the governor’s chair, Harris was back in the fray. He spent six years at the State Board of Education, another six years teaching mathematics at Sul Ross State Teachers College and three years as Superintendent of the San Benito public schools. With little time left, he retired again and died on Jan. 26, 1934.

A.W. Birdwell’s comments at Harris’ death capture the man to a T: “I have never known a man who was more absolutely honest both mentally and morally, and who exercised more courage in the discharge of his administrative duties.”

The 1910 Pedagogue editors had seen a more personal side: “T.G. Harris, the prominent educator, has the reputation of being as fastidious about his gloves as some women are about silk hose and lace handkerchiefs. He never wears the same pair more than twice. His fastidiousness may be attributed more to his generosity than to his vanity, however, for he always takes occasion to place his discarded gloves in some public place where any student who needs a pair may come along and take his choice.”

More information about his grave can be found at findagrave # 86033680.