EL CENTRO HISPANO DE SAN MARCOS

THE GIRL WHO WANTED A PIANO

Picture book celebrates Ofelia Vasquez-Philo’s Centro dream and legacy

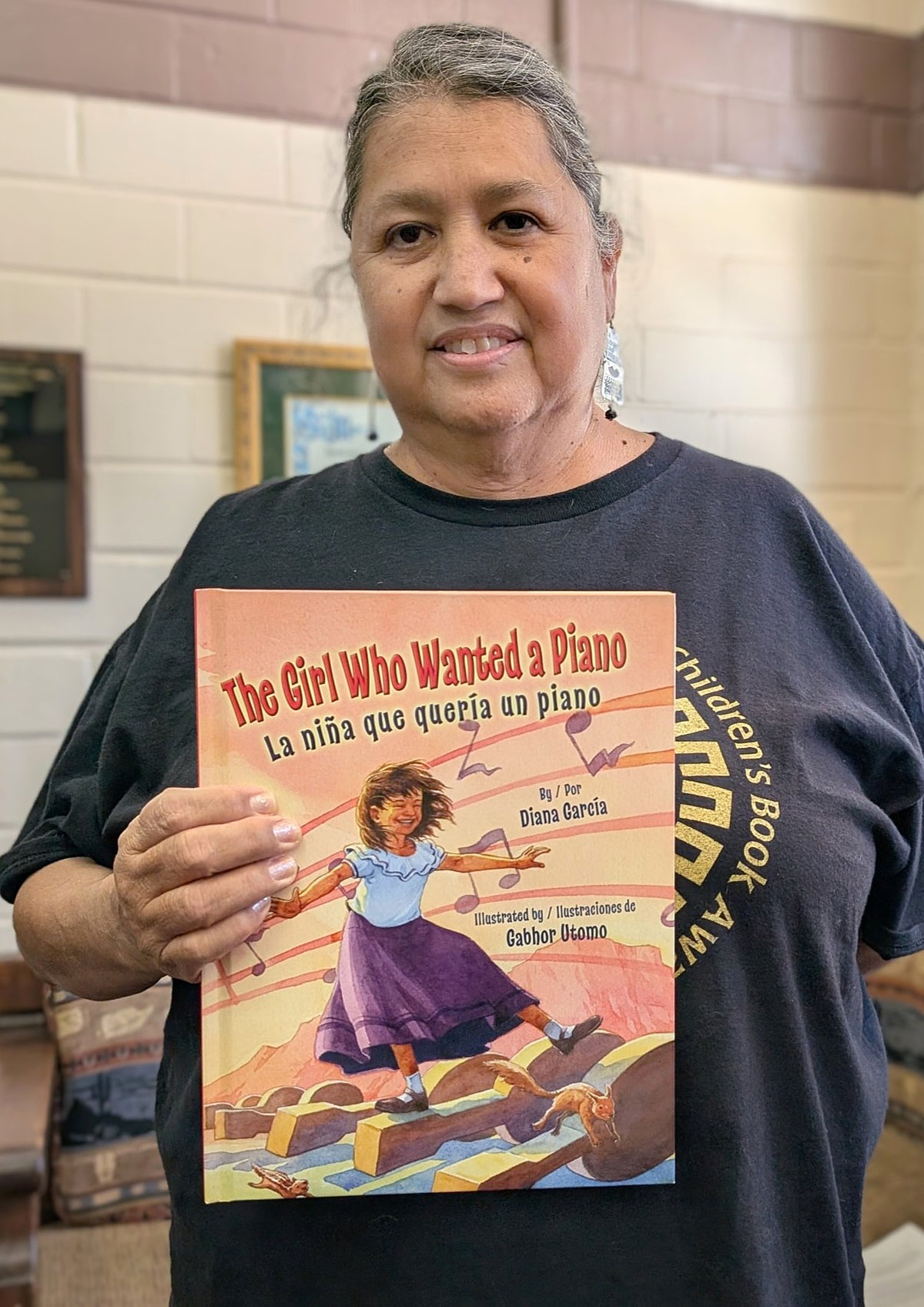

With her picture book “The Girl Who Wanted a Piano,” San Marcos teacher Diana Garcia pays tribute to the lasting legacy of local Hispanic culture advocate and Cetro co-founder Ofelia Vasquez-Philo.

The first Latina to serve on the San Marcos CISD school board, from 1969-1971, Vasquez-Philo was executive director of Community Action for more than 20 years and joined many community service organizations. She was an active member of the San Marcos League of Women Voters and the San Marcos Heritage Foundation.

“Ofelia was a force of nature,” said Linda Coker, current chair of the Hays County Historical Commission who served on the HCHC board alongside Vasquez-Philo. “A perfect lady, polite, reserved, logical and when you least expected it, she would somehow convince you that whatever it was she wanted, ie. El Centro, was exactly the dream you had too, just never knew.”

Garcia’s book portrays Vasquez-Philo as a young girl who yearned to learn how to play the piano, but her family could not afford one. Young Ofelia pretends her pillowcase is a keyboard and writes many songs about her life and dreams, but never learned to play an actual piano. As an adult, she recalls her childhood wish and opens El Centro Hispano de San Marcos to provide area children with the opportunity she never had

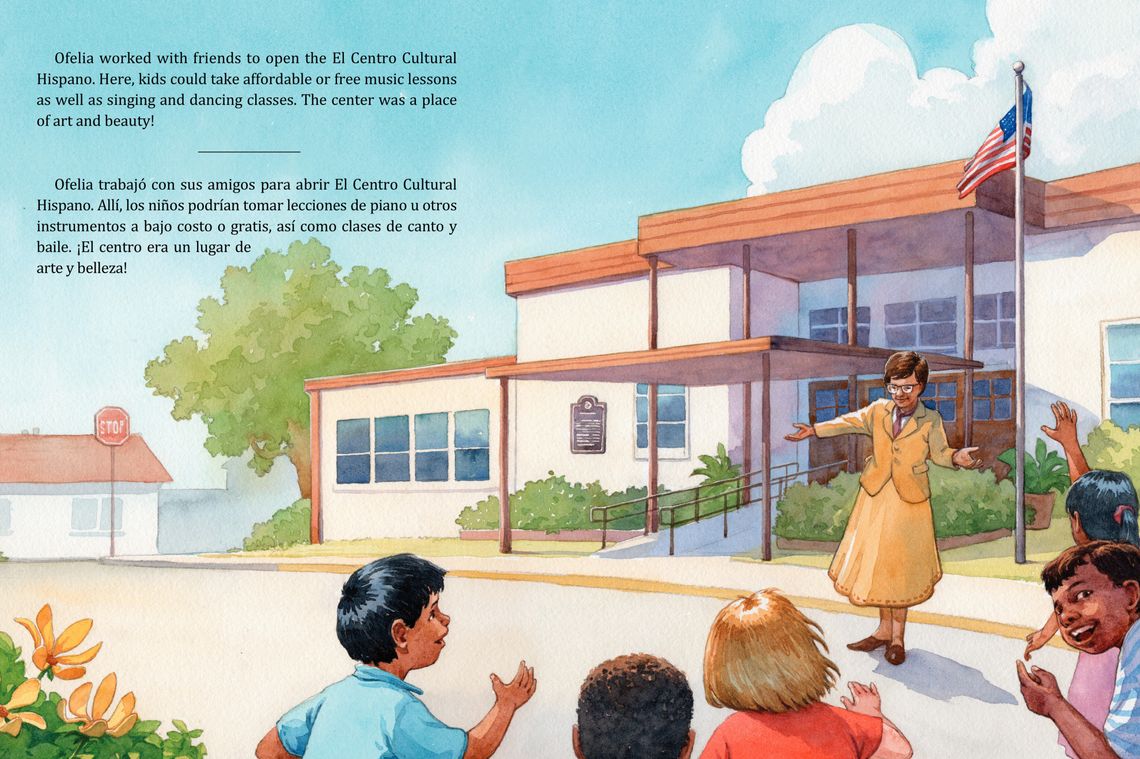

De Zavala Elementary teacher Garcia interviewed Vasquez-Philo several years ago, and this conversation became the inspiration for her book. While Garcia invented the “pillow keyboard,” Vasquez-Philo emphasized her love of music throughout her life. The final spread of the book, which Garcia said she wrote for second and third graders, is an illustration of an adult Vasquez-Philo welcoming children to El Centro.

The building currently housing El Centro was built in 1949 as Southside Elementary, a segregated school for Mexican- American students. Following a name change to Bonham Elementary in 1965, the school became one of the state’s first bilingual schools. In 2010, the building became El Centro Cultural Hispano de San Marcos, thanks to Vasquez-Philo and fellow El Centro cofounders Lupe Castillo, Rosina Ruiz Valle, Gloria Salazar and Margie Villalpando.

The mission statement of El Centro reflects the desire of the founders to not only provide music and dance lessons for students, but to create a cultural hub, a museum and living tribute to the Hispanic roots of San Marcos.

The heritage and language so proudly at the core of El Centro were often repressed when Ofelia was growing up in the San Marcos area in the 1930s. And still today, Garcia says some teachers and student parents discourage the use of Spanish at school.

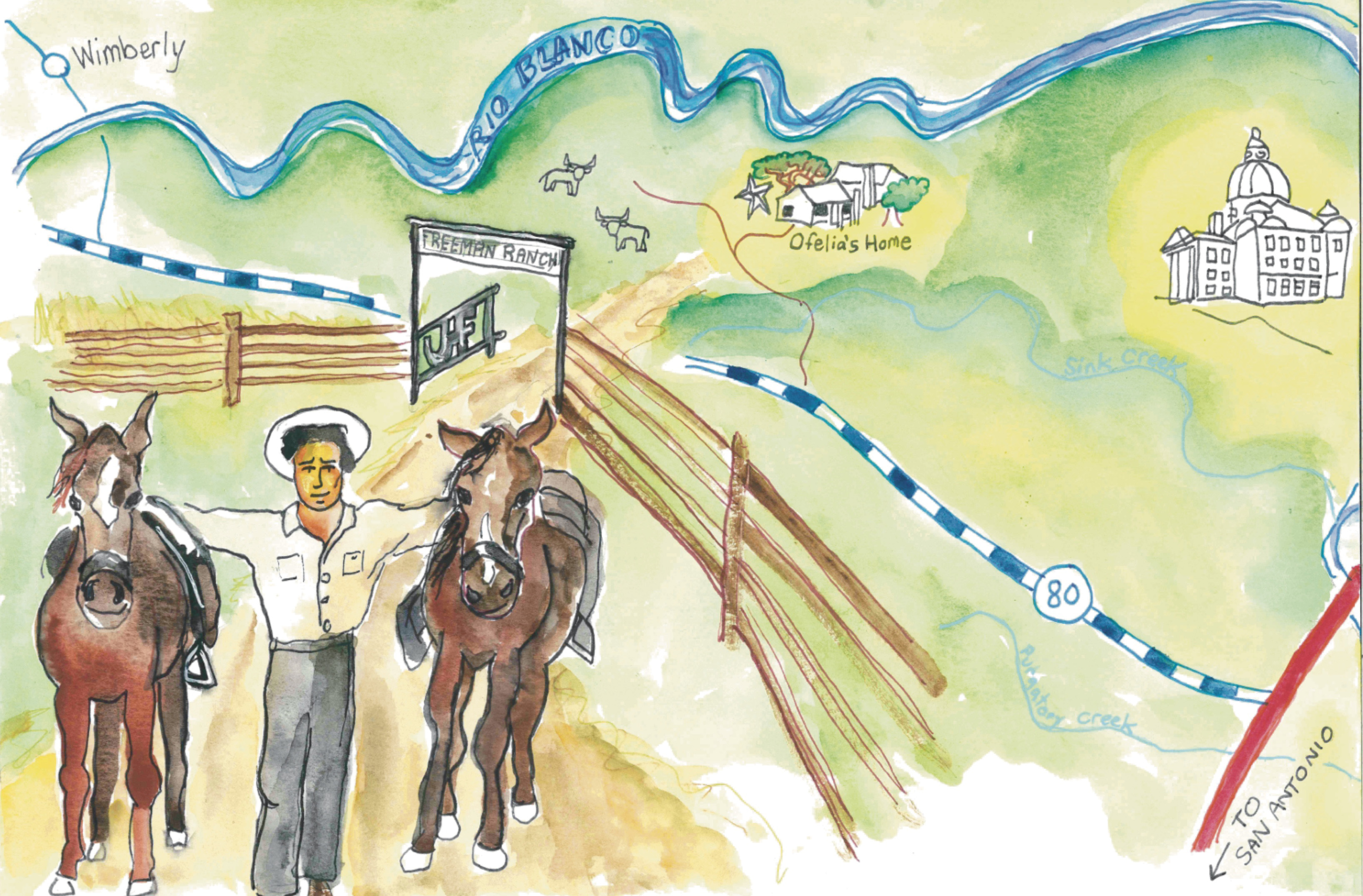

Born in Seguin, Ofelia moved to the Freeman Ranch, between San Marcos and Wimberley, when her father was hired as a ranch hand. She attended St. John’s Parochial School in San Marcos, where the nuns discouraged students from speaking Spanish. She and her siblings would stay in San Marcos with family friends on school nights and return to Freeman Ranch on weekends.

The Ranch had a storeroom for books and magazines, where Ofelia would hide out and read magazines like Reader’s Digest and National Geographic when she wasn’t doing chores around the ranch.

“I developed such a love for reading, because the more I read, the more I learned about this, that and the other,” she said in an oral history on the HCHC website. “I was reading how to do budget things and save money when I was nine and 10 years old, besides making butter.”

Like Ofelia, Garcia did some covert reading while she was growing up. Born and raised in San Antonio, she used to skip elementary school classes to go to the library. Later as a student at Sidney Lanier High School, her literary rebellion took the form of satirical writings about her teachers and principal, self-published in her underground zine called “Ink Spots.”

Alkek Library at Texas State University defines “zine” as "an independently- or self-published booklet, often created by a single person."

Her teachers at Lanier encouraged students to pursue vocational careers, but Garcia was determined to go to college and become a teacher, to inspire students in ways that the Lanier teachers had been unable to inspire her. As an English major at the University of Texas in Austin in the 1980s, she latched onto the similarities between the heavy metal music she grew up listening to and the burgeoning punk rock scene in Austin. She became a fan of Scratch Acid, the Big Boys and the Offenders, bands which expressed the angst and frustration that Garcia had experienced growing up in San Antonio. She soon joined the Austin music scene, playing drums and bass in Girl Robots and Gallus Mag.

Another prominent part of the punk/DIY underground movement in Austin at that time was the zine scene, proudly primitive odes to music, fashion and a grab bag of other obsessions, often xeroxed at the nearest copy shop.

Her zine “Bad News Bingo” was Garcia’s writing outlet during her time in Austin, and included her poems, essays and sometimes-dark observations as well as submissions from friends and fellow musicians.

Garcia has continued to write throughout her 30-year teaching career. She taught in Austin for 15 years after graduating from UT, before taking a teaching position at DeZavala 17 years ago.

In 2024, friend and Texas State University professor Jesse Gainer published her “Bottle of Spit, Five Urban Folktales,” on his Aquifer Cartonera imprint.

Like Vasquez-Philo, Garcia has been a community activist in the San Marcos area. She is a Calaboose Museum board member, and hosts an annual African American “Read In” at Cephas House during Black History month.

Garcia has also regularly attended events and workshops at El Centro, which is where she first met Vasquez-Philo, when she was giving a talk at a fundraiser.

“She was explaining how she always wanted to play the piano, but her parents were too poor, but she just always had this dream that if it couldn’t happen for her, she wanted to happen for other children, and that’s why she fought so much to get the Centro Cultural opened up here in San Marcos, so children could take piano lessons.”

Inspired by this positive role model for the Hispanic community in San Marcos, Garcia interviewed Vasquez-Philo to find out more about her dream, and how it led up to the founding of El Centro. The desire to learn the piano dated back to school years at St. John’s Parochial School, but the idea for El Centro was confirmed by a road trip to Mexico.

Ofelia went to Mexico City as a teenager, where she saw the Baile del Venenado (Dance of the Deer) at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, said Garcia. This dance, inspired by a Yaqui Indian ritual, depicts the slow and agonizing struggle of a deer against death after it has been shot by hunters.

“The deer doesn’t want to die, and the drum is going, slowly going, losing its beat as the deer fights against death. And at that moment, she thought, ‘That reminds me of my dream. I never learned to play the piano, but I can’t let that dream die.’” The tenacious battle of the deer against death inspired Vasquez-Philo to revive her dream and to eventually found El Centro. Which is why Garcia was disappointed when the publisher for “The Girl Who Wanted a Piano” decided to edit out the beginning section she had written about the Baile del Venenado.

Unfamiliar with the page limitations and editing protocols for publishing a picture book, Garcia had completed her story, which initially included a good deal more about the real-life childhood of Ofelia, before submitting it and reached out to an artist friend to illustrate it.

That friend, St. Louisbased artist Dawn Pulsipher, was seemingly the perfect person to illustrate the book, having played the piano as a child, developing a “deep connection with the instrument.”

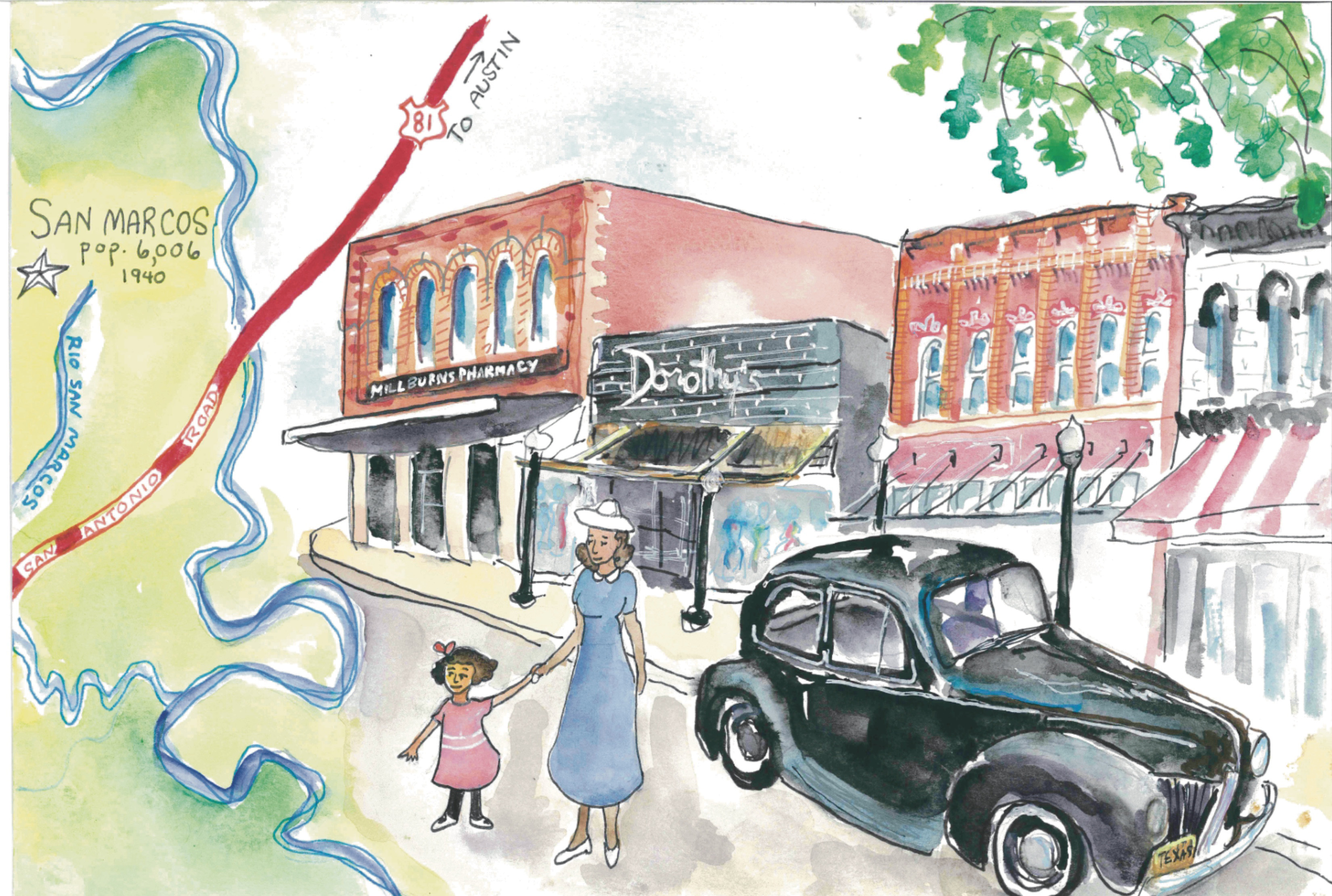

Pulsipher was also inspired by the historical context of the story, drawing a map of the Freeman Ranch and San Marcos areas, depicting the downtown buildings in San Marcos, even including the brand for the Freeman Ranch.

“I wanted to draw Ofelia’s world as a map, so I researched what the maps of the area looked like in 1950.”

“Dawn did beautiful art,” said Garcia. “I loved it.”

The first publisher who expressed interest in the book had requested that artwork be included with the story. But that publisher fell through, and Arte Publico Press, who did publish the book, had their own ideas about the content and the artwork.

“When she found her current publisher, they had edited out all references to Ofelia’s parents, her father’s job on the ranch, her mother playing guitar, her trip to Mexico, etc.,” said Pulsipher. “So my pictures didn’t fit anymore…. I felt like the professional artists they offered at the publisher would be a better choice.”

Garcia was disappointed in the publisher’s edits, especially the loss of the Baile del Venado section, which she felt was key to understanding what drove Vasquez-Philo to found El Centro. Garcia considered self-publishing the book, but ultimately decided that the version put forth by Arte Publico was her best option.

“I’m a really busy teacher. I don’t have the means or the energy anymore. Arte Publico Press has the resources to get the book in schools and libraries.”

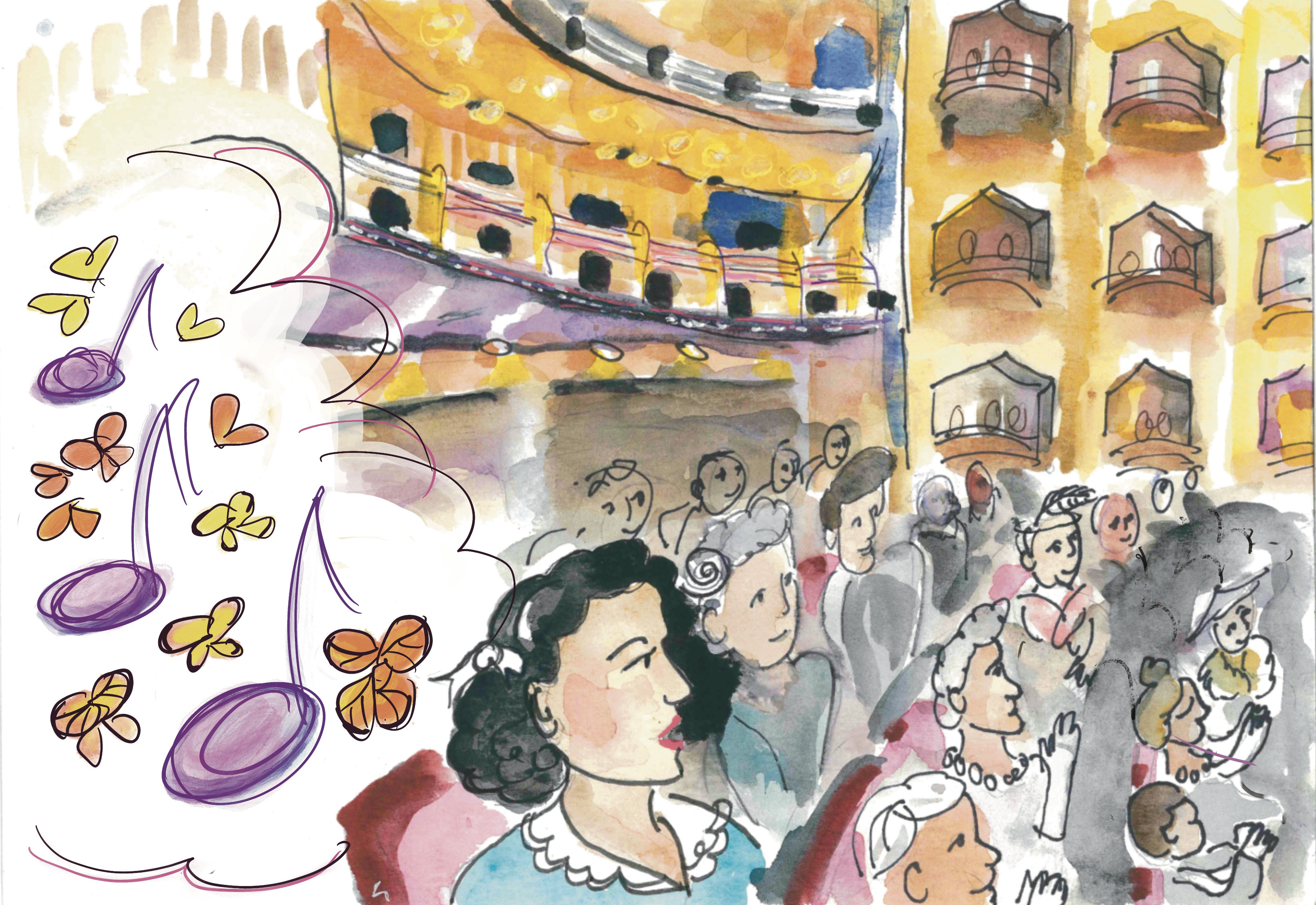

Ultimately, Garcia was satisfied with the artwork created by Gabhor Utomo, the Portlandbased illustrator the publisher matched with her book.

“I think he did a good job in how he shows the child’s happiness and musical notes. And I really appreciate the last page, which shows an adult Ofelia standing in front of a building that looks like Centro. He must have researched to see what the building looks like. So I really appreciate that.”

Utomo said that his drawings were rooted in the fanciful imagination of Garcia’s Ofelia character.

“When I started sketching for the book I wanted to highlight Ofelia’s imagination because in the story Ofelia’s imagination helped her overcome her situation,” Utomo said.

“When I first read the story I thought it was very inspiring. I love that even though Ofelia Vasquez never had a chance to learn to play piano, she made it possible for other kids to learn,” according to Utomo.

Garcia did stand firm on two of her initial plans for the book. The last page of the book contains a brief bio of Vasquez-Philo, highlighting her importance to the Hispanic community in San Marcos as well as the rest of Texas. And that bio shares the page with a Spanish translation. And so does the rest of the book, each English passage echoed by the Spanish version.

Garcia’s hope, and one expressed many times by Mrs. Philo, is that Hispanic students will take pride in the Spanish language, as well as in their history and culture.

Soon after the book was published, El Centro hosted a release party for “The Girl Who Wanted a Piano/La niña que quería un piano,” (to use the full title) with Garcia reading the book in both English and Spanish to a packed house.

Among the audience for the reading was Rosina Valle, co-founder of El Centro and niece to Vasquez-Philo.

“Diana did a great job capturing my aunt’s love of music,” said Valle. “Our families were both very appreciative of music and the arts. Aunt Ofelia poured her heart into the creation of Centro, advocating for a place for children to experience music, dance and the arts.

“Additionally, She was a strong advisor of supporting and mentoring women. She always believed you have a voice and need to feel empowered to use it,” Valle said.

With her voice, Diana Garcia has published “The Girl Who Wanted a Piano,” to share Ofelia’s dream and inspiration with young readers.

Ofelia Vasquez-Philo died in 2017, but her legacy lives on at El Centro.