The imminent Permian Highway Pipeline project by Kinder Morgan that has been in the works since fall 2018 threatens to start construction as soon as they have federal permits, which are expected soon. However, the $2 billion, 42-inch natural gas pipeline that is set to run through multiple counties, including Hays, Gillespie and Blanco, has put a number of concerns on the minds of many Texas Hill Country communities and landowners, leading to a lawsuit filed on Feb. 5 by multiple cities, districts, property owners and Hays County.

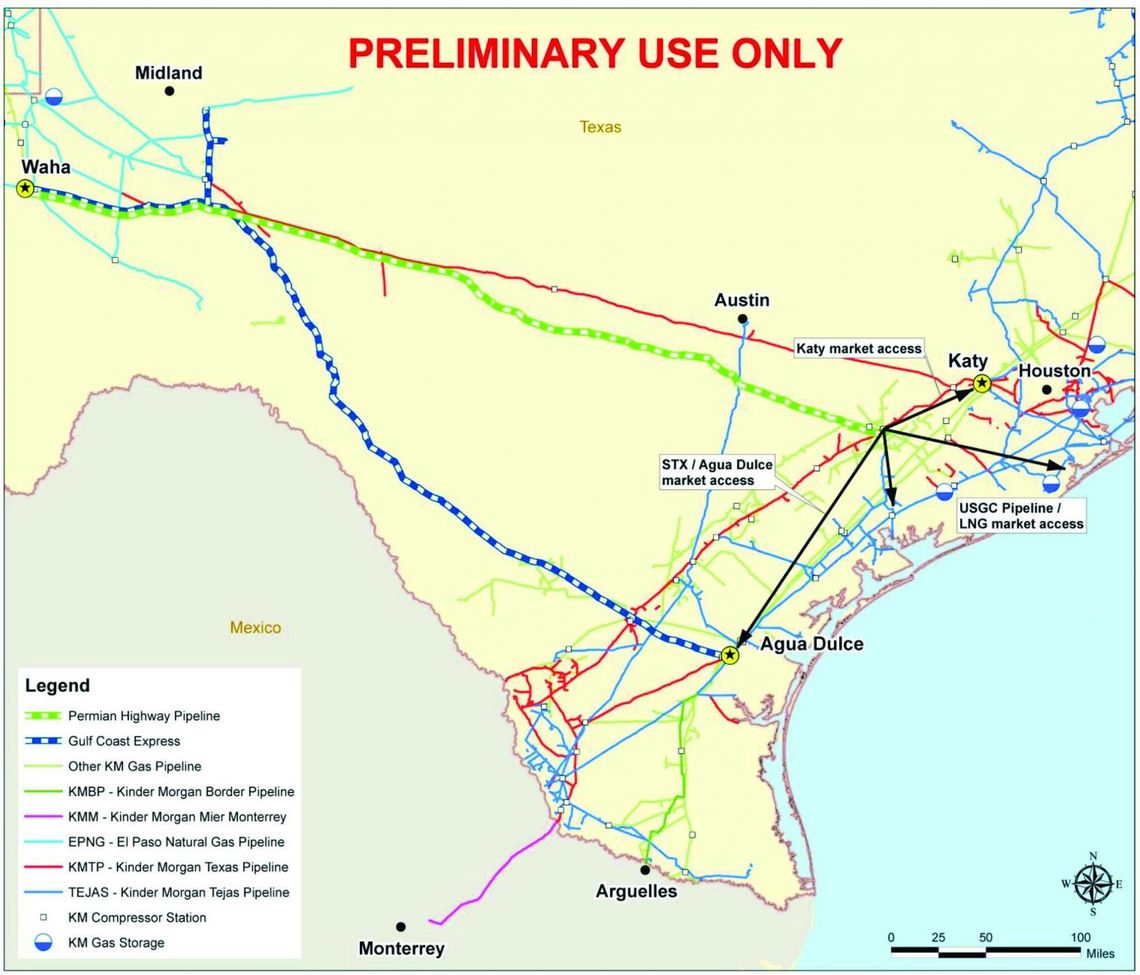

Kinder Morgan, an energy infrastructure company specializing in oil and gas pipelines and terminals, said in a press release that the Permian Highway Pipeline (PHP) will help increase natural gas production from the Permian Basin to the up-and-coming markets along the Texas Gulf Coast.

“We are committed to supporting development of the infrastructure needed for our planned production growth in the Permian Basin,” Sara Ortwein, president, XTO Energy, said in the press release. “The Permian Highway Pipeline will provide additional capacity for reliable transportation of natural gas to the U.S. Gulf Coast.”