There are a plethora of moving pieces involved in solving crime, and those behind the scene play a large part in the application of justice.

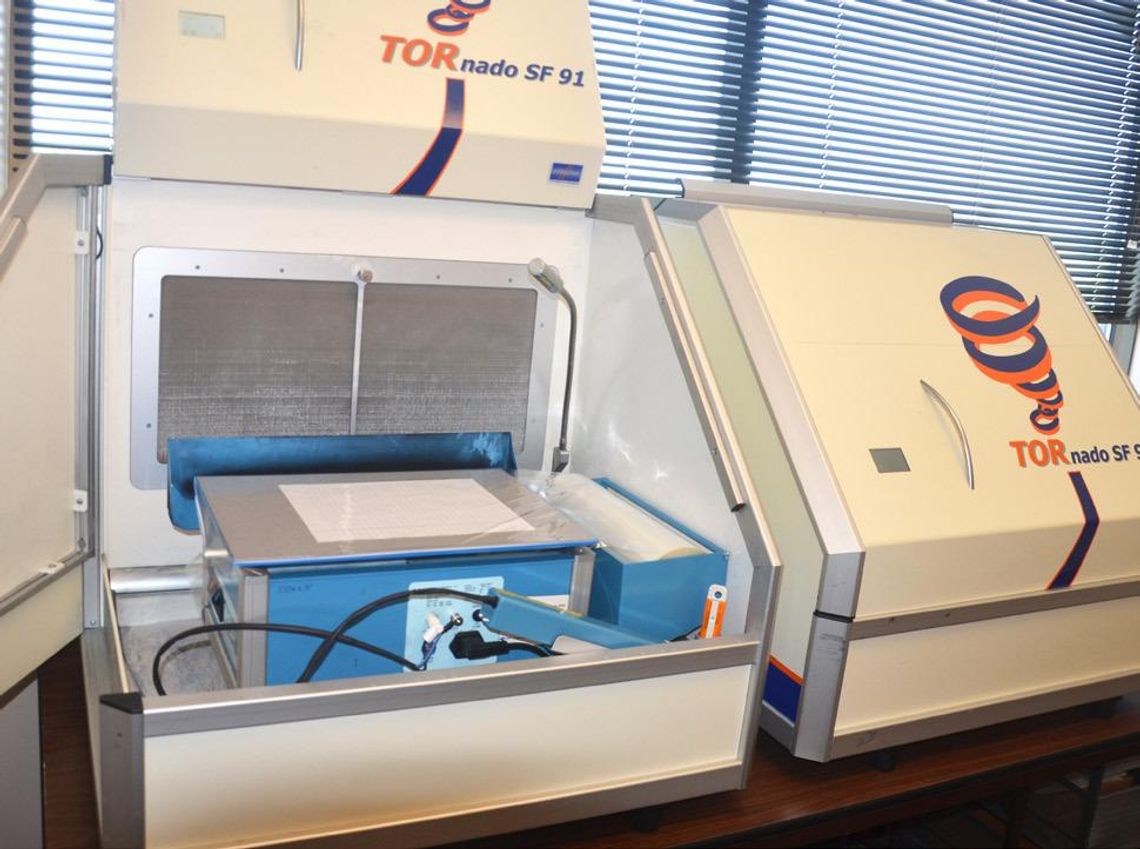

For National Forensic Science week, the Department of Public Safety Forensic Crime lab in Austin– which services all of Central Texas, including San Marcos, lifted the curtain to provide the public a peek into what it is that they do.

Each department has its own specialization and plays its own pivotal role, which in concert can uncover the who, what, where, when and how of a crime.

PLEASE LOG IN FOR PREMIUM CONTENT. Our website requires visitors to log in to view the best local news.

Not yet a subscriber? Subscribe today!