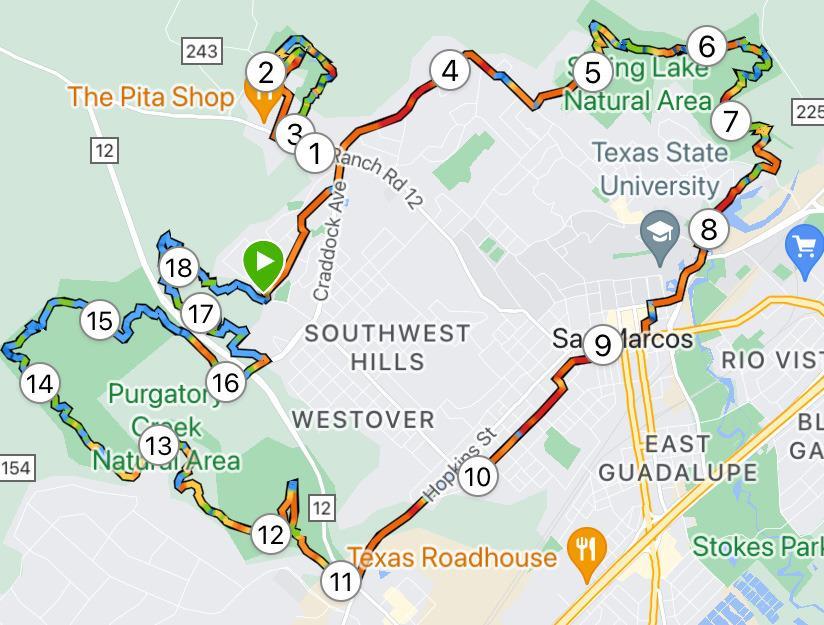

A map of the San Marcos Traverse as diagrammed by Christian Hawley

Christian Hawley hiking with his children.

Photo courtesy of Christian Hawley

The pond at Ringtail Ridge between the berms hosts hundreds of black-bellied whistling ducks

Photo courtesy of Christian Hawley

The San Marcos Traverse

Creating an 18-mile loop to run around town

The most prestigious race in the trail running world is the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc covering three countries, 106 miles and 33,000 feet of elevation gain. This is not that, but it does share in the wisdom that to truly know a place is to run around it.

The most incisive essay about faith and geography is the Rev Michel de Certeau’s “Walking in the City,” where he contrasts the image of God as a great architect in the sky with the image of God as a lowly ground pounder wandering the social trails of New York City. This is not that either, but it does share in the wisdom that to see the soul of a town is to walk not the grid but the trails carved by the stories of its inhabitants.

The San Marcos Traverse is the dream of a trail-running priest trying to get to know the soul of his village. My family and I moved here twenty months ago when I took the job as the new rector at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church out on Ranch Road 12. On Feb 17, I finally got around to running around our town, and here’s what I found.

It is hard to see a ringtail cat at Ringtail Ridge, but there is plenty of wildlife and pioneer spirit to be found here. While I was studying Buddhism in Nepal, I read Peter Matthiessen’s Snow Leopard, and the ringtail cat has taken on that kind of mystical pursuit in my life. Ringtail Ridge sits only a few miles from our house, so I often join my spouse and kids out there in the early morning hoping to catch a glimpse of this shy Texas native. I’ve had no luck to date, but we have seen deer, armadillos and even porcupines from the little boardwalk. On this particularly blustery morning, the ponds between the berms host hundreds of black-bellied whistling ducks whose chatter makes me feel like I’ve interrupted an international Ducks Anonymous convention. There is a wildness to this park you can’t find in any of its urban cousins in Austin or San Antonio. Part of the wilderness feel derives from the ranching ephemera abandoned in place, but most of the impression is due to the hardscrabble trails. A hike around the ridge feels less like a scenic tour, and more like tracking a lost calf down cow paths full of rocks and cactus. It’s not hard to grasp the grit and gumption of the earlier European settlers of San Marcos as you walk around this pioneer park interacting with all sorts of critters.

If Ringtail Ridge speaks to the pioneer spirit of our town, then Spring Lake speaks to something much older and deeper, like aquifers and ancestors. I love entering this Natural Area via the North LBJ entrance — a kind of secret garden gated portal that meanders past a shrieking shack and then, like an upstart creek, careens down switchbacks named after roadrunners and porcupines. In this part of the park, all waters flow toward Sink Creek, cli- maxing in the unexpected waterfalls called the Cascades. The sound of water, the fertility of the bottom lands, and the eventual overflow into Spring Lake make it easy to understand why this is one of the longest continually inhabited places in the country.

This landscape sings of life and vitality, and perhaps that’s why the Indigenous Cultures Institute sited their repatriated remains cemetery here. As a priest who’s attended almost 100 deaths, I’ve come to appreciate the beauty and serenity of final resting places. One of my favorite holy scriptures is the book of Tobit, because it’s where we get the final act of corporeal mercy — burying the dead — the only act that can never be repaid. Tobit recovers, repatriates and redeems his people with a proper burial in the earth. As I sit by the Lime Kiln entrance to this park next to the gated circle of stones reading “Ancestor,” my respect blooms for a people who live and die in the sacredness of a particular place. San Marcos, more than any other town I’ve lived in, is a town intimately connected to its place — to the land, to the headwaters and ultimately to the river. I’m still trying to understand and embrace this flow, an endeavor that will undoubtedly and delightfully take the rest of my life.

My next stop is Purgatory Creek almost four miles southwest of here, but before I press on the voice of my old Liberation Theology professor, Dr. Fernando Segovia, checks me up. Dr Segovia was the senior advisor on my thesis exploring post-imperialism. I’m a U.S. military veteran of English and Italian lineage, so from Forum to Parliament to the Pentagon, it's hard for me to be more imperial. Dr. Segovia was fond of asking, “Who’s not at the table,” or in the case of geography, “Who does not have easy access to protected natural areas.” And the answer to that question in this part of the world, in my opinion, is people east of I-35. I’m really only running around half of our town, a choice dictated by my old, airfield knees, and the lack of any long unpaved trails on the east side of San Marcos. This is a good place to live, but it is not free of the lingering prejudices that sited airfields and wastewater treatment facilities in the poorer and traditionally darker-skinned parts of the town. The soul of this town still has reconciling work to do, and I hope I can be part of that hard, but holy work.

Speaking of holy, my route to Purgatory Creek Natural Area passes by M&M Taco Corner, where I meet my family for a few tacos and some moral support. Renewed by children’s laughter and chorizo and egg tacos, I make my way to the Lower Purgatory Creek Trailhead, a statement which tickles a Dante scholar friend of mine to no end. Daniel Strandlund served as the priest of St Elizabeth Episcopal Church in Buda, and has now moved on to graduate work at the University of Nottingham on Dante Alighieri. Over a few beers at Roughhouse Brewery a couple of years back, I asked Daniel if he could map out a route through Purgatory Creek that would trace Dante’s Divine Comedy from the Inferno to Paradiso. Alas, no such directly corresponding route exists, but there is a little something for everyone from heaven to hell on this trail system.

I spend most Wednesday mornings hiking Lower Purgatory with VetRecOutdoors, a nonprofit that helps veterans find community and healing on the trail and the river. Some weeks we’re hiking alone in the inferno of a Texas summer or the inescapable mire of Del Rio clay after a torrential rain. Other weeks, we find ourselves accompanied by college coeds with their puppies or seasoned birders moving in binoculared flocks. On this Traverse Saturday, I take the heavenly path, which shares its name with my grandmother, Beatrice Barzetti, to the secluded paradise of the Paraiso Trail before popping out at the gravel parking area of Upper Purgatory. From the fossil bed treasury my kids play in along the Ripheus Trail to the ADA-compatible Styx Trail I bring all of my old parishioners out on for a Christmas Hike, Purgatory Creek Natural Area speaks to the diversity and adaptability of our town to offer all people, of all walks a life, a chance to interact with God, their neighbors and all of creation.

Buoyed by this hopeful spirit of adventure for all, I turn toward home and the newest park in San Marcos, River Recharge Natural Area. This little pocket park at the end of Bishop St. is why we stretched ourselves to the absolute limit to buy a house in the neighborhood. I spent my formative years gallivanting around a homestead straddling the Ohio/West Virginia border where we raised goats, rabbits, chickens and ducks alongside a giant garden. My younger sister and I wandered free range over acres of forests, ponds, junk yards and livestock pastures. My kids won’t have that experience, but they will be able to live and play by a wild space that will feed their imaginations, test their courage and give them a healthy relationship with the land.

My five-year-old daughter has gotten into Winnie- the-Pooh, and it does my heart good to hear her refer to the RRNA as our Hundred Acre Wood. As I close the loop on my traverse, I imagine her dragging her stuffed animals out to the motte of oaks along the southern reaches of the Doline Trail or going on an expedition into Karst Canyon looking for Heffalumps. It also does my heart good to be part of a community who is still building trails. I recently invited the San Marcos Greenbelt Alliance chief trail builder, Todd Derkacz, out to the church to see if we could develop a trail on the 20 acres we own adjacent to San Marcos Academy and First Christian Church. While bushwhacking our Back 20, Todd asked me why I wanted to put trails in here. I responded because I wanted a place for people to find peace and communion with something bigger than themselves.

“Just for your church people,” he probed.

“No, for all people,” I replied. Todd smiled and said he could work with that. This is that. That spirit of curiosity and humility dedicated to discovering and sharing the joy and responsibility of walking this earthly pilgrimage with God, our neighbors and ringtail cats (if they really exist).

I finish the San Marcos traverse where I began, the newly constructed timber frame kiosk at the end of Bishop St, and I’m reminded of TS Eliot’s Little Giddings Poem: “And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started, and know the place for the first time.” I think I know San Marcos a little better, and I like it even more.